Mike and I logged just under 6,000 miles in the 30 days we were gone, from September 21 to October 22. We stayed at Mike’s folk’s house in Greenbrier for a combined eight days, and for three days with Gary and Tracy Vaughn in Louisiana. We stayed with sister Raine and her husband Chris for two days – one day going and one day on the way home. We lingered two nights each in Moab, Pocatello and Baker City. The other 17 days were all one-night stands: setting up, settling in, and breaking camp the next morning. We found RV parks on our GPS, and made up the rest as we went.

Kyla’s Top Five: Visiting Raine and Chris and the Heart Tree in Hailey, Idaho; ogling the ruby slippers in the Oz Museum in Wamego, Kansas; tagging monarch butterflies in Kansas City, Missouri; rousting through flea markets with Peggy in Greenbrier, Arkansas; and snuggling in the RV with Pip to write blogs.

Mike’s Top Five: Standing in the six-foot Guernsey wagon ruts in Wyoming; visiting his folks in Greenbrier, Arkansas; exploring Fort Laramie in Wyoming; riding into the history of the Pony Express Museum in Marysville, Kansas; and turning a gas shortage into a pleasant experience on South Pass, Wyoming.

We’ve probably forgotten more than we remember, ate more junk food in a month than the entire previous 12 months combined, and learned to work as a team, capitalizing on each other’s strengths and picking up the slack whenever needed. We both experienced highlights that will stay with us forever. For my part, I’ll remember the freedom of being self-contained, figuring out the promises and problems of each day, and letting the wind blow us where it would.

Our Map:

V: Bend, Oregon

B: Idaho City, Idaho

S: Hailey, Idaho

D: Provo, Utah

E: Moab, Utah

F: South Park, Colorado

G: Garden City, Kansas

H: Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

I: Greenbrier, Arkansas

J: Alexandria, Louisiana

K: Greenbrier, Arkansas

L: Springfield, Missouri

M: Topeka, Kansas

N: Fairbury, Nebraska

O: Gothenburg, Nebraska

P: Glenrock, Wyoming

Q: Kemmerer, Wyoming

R: Pocatello, Idaho

S: Hailey, Idaho

T: McCall, Idaho

U: Baker City, Oregon

V: Bend, Oregon

Scroll around our map, below:

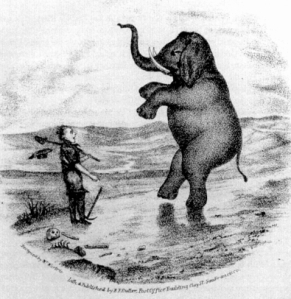

The Columbia River could swallow them whole, in an instant, never to be seen again. Men, women, and children – alike and without discrimination. When pioneers on the Oregon Trail had traveled over 2,000 miles, through sand and storm, draught and disease, they reached The Dalles, in the promised land of the Oregon Territory. Only 150 miles remained between them and their destination in Oregon City. But first, in The Dalles, a critical decision had to be made: Raft their wagons down the untamed Columbia, or take the cold and rugged Barlow Trail over Mt. Hood? Their lives might very well depend on the route they chose.

The Columbia River could swallow them whole, in an instant, never to be seen again. Men, women, and children – alike and without discrimination. When pioneers on the Oregon Trail had traveled over 2,000 miles, through sand and storm, draught and disease, they reached The Dalles, in the promised land of the Oregon Territory. Only 150 miles remained between them and their destination in Oregon City. But first, in The Dalles, a critical decision had to be made: Raft their wagons down the untamed Columbia, or take the cold and rugged Barlow Trail over Mt. Hood? Their lives might very well depend on the route they chose.

The Barlow Trail – Then and Now

The Barlow Trail – Then and Now